How do Europe’s financial markets today compare with the rest of the world’s?

How do Europe’s financial markets today compare with the rest of the world’s?

Europe enjoys an advantageous geographical position among the world’s financial markets, in a time-zone that straddles the US and Asia-Pacific trading days. While this continues to be a key differentiator attracting global investors to our markets, the reality is that Europe has lost some of its competitive edge in recent times.

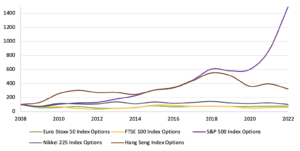

For instance, the volume gap between European equity and equity derivative markets and their US and Asian counterparts is widening. A striking example is benchmark index options volume, which surged in the US but remains muted in Europe.

Global Index Options: Total Annual Notional Traded

Source: Bloomberg LP

Note: Normalised to 100

We think that with the right approach, Europe can once again excel and boost its attractiveness as an investment destination. I would caution though that there is no silver bullet or quick fix.

Where should Europe look for further growth opportunities?

Increased retail participation has been a key contributor to growth in other regions. We think a solid retail investor base exists in Europe too and would grow with the right mix of reforms that promote long-term investment and stimulate primary markets. This will take work, but it’s worth it in our view.

For example, there should be more emphasis on promoting exchange-traded products like listed equities, options, futures and ETFs to retail investors. Some reforms, such as Germany’s recent ban on certain types of futures for retail traders may have the opposite effect and draw volume to structured products such as CFDs, turbos, warrants and sprinters, which lack transparency and can be more costly.

There is also is plenty of opportunity for Europe to grow its institutional investor base, particularly through measures that encourage trading to shift from OTC to venues. Some listed derivatives, for example, are subject to burdensome margin requirements, which only serves to promote OTC alternatives.

More broadly, European regulation is littered with complex and overly prescriptive measures, such as the share-trading obligation and mandatory buy-in regime. These rules do not exist anywhere else in the world and may discourage firms from investing in Europe and lead EU-based firms to relocate or seek opportunities elsewhere

What specific initiatives should exchanges and other market participants pursue to boost European capital markets?

“Big tech” stocks, which tend to be popular among retail investors, are almost exclusively listed in the US. Europe’s struggle to attract these IPOs could be the result of inflexible listings regimes, burdensome prospectus rules, barriers to cross-border investments, and divergent withholding tax and insolvency regimes across member states. Tackling these issues is vital to enhancing European primary markets and could help the bloc become a pre-eminent listing destination for emerging sectors like clean energy, biotech and medtech. We hope the EU’s Capital Markets Union and related Listing Act proposal can help in this regard.

Trading venues should also play a role, for instance by adding products that cater to the diverse needs of investors. Examples of this are short-term or daily options, which have seen success in the US, or exchange-listed variance swaps, a product that is typically traded OTC. More generally, it’s important to arrive at a market structure that promotes competition among market makers and participation from retail and institutional investors alike.

What role should European policymakers play in tackling the region’s growth problem?

Inconsistent regulatory approaches across European member states brings increased complexity, leading to sub-optimal investor outcomes. A case in point are the single market-maker arrangements that exist on some German exchanges, which we find problematic and raise questions around best execution.

Generally, Europe would benefit from moving toward a simplified and less restrictive regulatory regime that promotes competitive markets. There is a single rulebook but no single supervisor, leading to diverging national interpretations of regulations and market structure. All of this resulting in a high barrier to entry for smaller firms and an overly complex market structure that could deter non-EU institutions from becoming meaningful participants.